If a hypothetical 30th-century historian wanted to learn about your 21st-century life, they would have a harder time than they would trying to learn about Ronald Reagan or Pope Francis, but that does not mean they would be totally out of luck. Because even as an ordinary average person, you’ve left behind quite a paper trail. Every time you’ve bought a car, rented an apartment, refinanced your house, or taken out a student loan, you have generated a record that tells a little bit about your life. If a future historian had access to enough of those records, they might even be able to tell a lot about who you were.

The fact that Brown’s book focuses on the lives of ordinary people makes it different from much of the scholarship on the period, which has often been centered on aristocrats like kings, queens, or dukes, but has been especially focused the Catholic Church and its officials.

“We have a lot of records from the top down and from inside religious institutions,” Brown says. “Kings wrote a lot, and churches and monasteries kept documents that kings produced. And churches and monasteries wrote an awful lot on their own behalf, so we have a fair idea of what kings did, and we have a really good idea of what churches and monasteries did. Ordinary laypeople also used documents, but because lay families don’t survive for centuries like churches and monasteries do, their records have been lost or discarded over time. Our picture of their lives is almost entirely dominated by an ecclesiastical filter. If we see laypeople doing something, it’s because they’re doing something that a church was interested in and that the church wanted to keep a record of. This has always frustrated me, because the inevitable result is that when modern historians write about the early Middle Ages, three-quarters of what they’re writing involves churches, monasteries, bishops, monks, abbots. But that’s only part of the picture.”

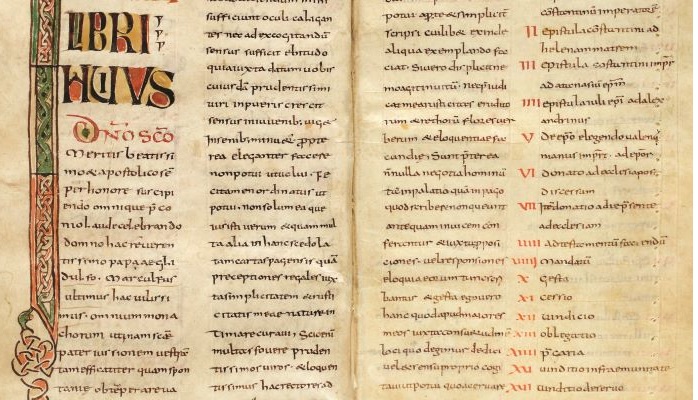

These days, if you want to easily take care of something like making a living will, registering for a trademark, or filing paperwork to incorporate a business, you might visit a website like LegalZoom, which has premade legal documents available for a fee. In the Middle Ages, monasteries played a similar role, and commoners went to monasteries when they needed a legal document prepared. To meet this demand, the monasteries maintained their own versions of LegalZoom, namely the collections of document forms and models, or “formularies,” that represent Brown’s main source.

“What’s surprising—particularly given modern stereotypes about the illiterate Dark Ages—is just how pervasive writing was,” Brown says. “These documents cover all sorts of conceivable circumstances, and they don’t just involve members of the upper classes. We see middling landowners and poor farmers as well as their unfree tenants, servants, and laborers too. They may not have been able to write themselves, but they knew bloody well what documents were, they knew who to go to when they needed one, and there’s evidence that they kept them. For example, if a lord frees one of his unfree servants, a document is produced, and that servant is going to keep it. Very few actual documents like this survive because the institutions whose records we have—mainly churches and monasteries—were not involved in the transactions that produced them. But the formularies give us an idea of what they looked like.”

Brown says the trove of document models he has analyzed cover not only economic transactions, like property sales, gifts, or exchanges, but also such things as marriages, divorces, parents leaving property to their children, childless couples leaving property to each other, a father making sure his disabled son is taken care of after he dies, elderly people adopting younger adults in exchange for being taken care of in their old age, disputes between neighbors, and much more.

So, what do these documents tell Brown about life in the early Middle Ages? Well, one thing that surprised him is that they show women wielding more independent power than you might expect.

“You often see women producing their own documents or being presented as principals in legal transactions,” he says. “They weren’t just appendages of their husbands. You see women appealing directly to the king for help and being able to travel over wide distances. It’s striking just how much agency women had. I didn’t expect it.”

The documents also show that violence was a much more regular feature of people’s lives than it is for us.

“We live today in a society where the state has a monopoly on the use of force,” he says. “If I were to come over and punch you, that would be illegal, but at a time and place when the state is much weaker than it is now, people had a fundamental right to use force on their own behalf, to take vengeance, or to defend themselves.”

Though violent acts could be expected, they were not unregulated. A person could only kill or harm another for what the community thought was just cause. Violence had to take place within a legal framework, and there was always a price to pay.

“If you killed somebody, you would have to pay for them. It’s called the blood price,” Brown says. “If I killed your brother, I may have thought I had a good reason, but you and your family are very angry with me, and you’re going to come after me unless I agree to pay you a certain amount of money to settle the debt. These amounts of money are specified in law. So, I’ll pay you the money, and you’ll write me a receipt that says you got it and that I’m free from any trouble about the matter. We only know about these receipts because they show up in the formularies.”

Brown says the era was also one in which patronage and nepotism were not just rampant but were acceptable and even necessary means for those who did not have power to gain access to those who did. If you were a peasant with a problem that needed solving, you might appeal directly to your king, whether by getting someone to send a letter for you or by walking 60 miles to make your request in person at the king’s court. More often, however, you would appeal to your lord or to your local bishop or abbot, who might have a relative who knew someone at court who could get the king’s ear.

“Patronage and nepotism were very real and powerful things. If you knew or were related to somebody who had power, or you knew somebody who was related to somebody who had power, you went to that person and you begged and pleaded, and that person would intervene on your behalf. It’s just the way society worked,” Brown says. “It’s how you get things done. And it happened at all levels of society. I’ve got a whole collection of letters written by a local lord in the 820s, where you can see him writing the most prosaic letters like, “So-and-so came to me and said, ‘He really would like to buy your pigs. Would you be willing to sell him your pigs?'” People were appealing up the chutes and ladders of power to get things done in a way that we today, I think, would look on with suspicion.”

If this all sounds to you a bit like a mafia movie, with people asking favors of the don and others engaging in violent acts to settle their differences, you’re not far off.

“It’s a little caricatured, but you can get pretty close to understanding the early Middle Ages by watching The Godfather,” Brown says. “The mafia also channels power along the lines of kinship, patronage, and protection, and it has rules regulating violence among its members. The difference is that it operates outside of the dominant system of law and order—and preys on it for profit. In early medieval Europe, it’s just simply how things worked.”

Source – Caltech

Auto2 years ago

Auto2 years ago

Auto2 years ago

Auto2 years ago

Technology2 years ago

Technology2 years ago

Auto2 years ago

Auto2 years ago

Lifestyle2 years ago

Lifestyle2 years ago